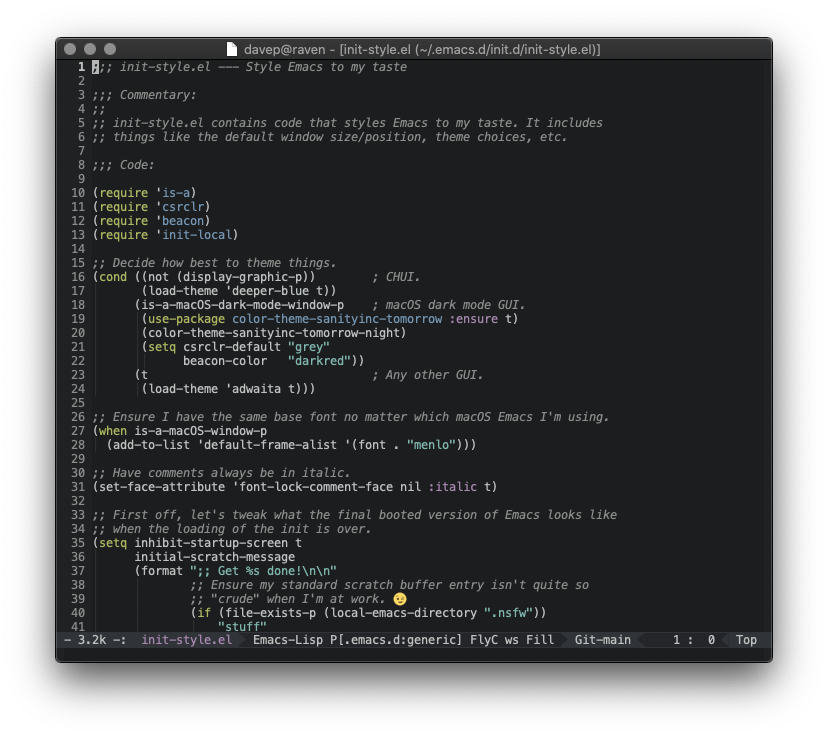

Although I read up on it a few days back, it was only this evening that I fired up Emacs (well of course I'm testing Swift with Emacs, what did you think I'd do?!?) and dabbled with some code to really get a feel for how casting works in Swift.

Swift seems to be one of those languages that does it with a keyword rather

than a non-keyword approach. The two main keywords being as? and as!. I

kind of like how there's a polite version and a bossy version. Having the

two makes a lot of sense from what I read too.

To try and illustrate my understanding so far (and do keep in mind I'm not writing this with the express purpose of explaining it to anyone else -- I'm writing this to try and retain it all in my head by working through it), here's a bit of utterly pointless and highly-contrived code that defines three classes in a fairly ordinary hierarchy:

class Animal {}

class Dog : Animal {}

class Cat : Animal {

func beAdorable() {

print( "Purrrrrr!" )

}

}

So, so far, so good: we have animals, we have dogs which are a kind of animal, and we have cats, which are also a kind of animal, but they have the special ability of actually being adorable. 😼

Now, for the purposes of just testing all of this out, here's a horrible function that makes little sense other than for testing:

func adore( _ a : Animal ) {

( a as! Cat ).beAdorable()

}

Given an animal, it forces it to be a cat (by casting it with as!), and

then asks it to be adorable (because, of course, cats always do as they're

asked).

So, if we then had:

adore( Cat() )

we'd get what we expect when run:

Purrrrrr!

So far so good. But what about:

adore( Dog() )

Yeah, that's not so good:

~/d/p/s/casting$ swift run

[3/3] Linking casting

Could not cast value of type 'casting.Dog' (0x10a1f8830) to 'casting.Cat' (0x10a1f88c0).

fish: 'swift run' terminated by signal SIGABRT (Abort)

One way around this would be to use as?, which has the effect of casting

the result to an

Optional. This

means I can re-write the adore function like this:

func adore( _ a : Animal ) {

( a as? Cat )?.beAdorable()

}

Now, if a can be cast to a Cat, you get an optional that wraps the

Cat, otherwise you get an optional that wraps nil (hence the second ?

before attempting to call the beAdorable member function).

So now, if I run the problematic dog call above again:

~/d/p/s/casting$ swift run

[3/3] Linking casting

In other words, no output at all. Which is the idea here.

I think I like this, I think it makes sense, and I think I can see why both

as! and as? exist. The latter also means, of course, that you can do

something like:

func adore( _ a : Animal ) {

let cat = a as? Cat

if cat != nil {

cat!.beAdorable()

} else {

print( "That totally wasn't a cat" )

}

}

which, in the messy dog call again, now results in:

~/d/p/s/casting$ swift run

[3/3] Linking casting

That totally wasn't a cat

Or, of course, the same effect could be had with:

func adore( _ a : Animal ) {

if a is Cat {

( a as! Cat ).beAdorable()

} else {

print( "That totally wasn't a cat" )

}

}

It should be stressed, of course, that the example code is terrible design, so given the above I'd ensure I never end up in this sort of situation in the first place. But for the purposes of writing and compiling and running code and seeing what the different situations result in, it helped.