Check this out, it's a test post!

Useful information with formatting and links.

Helpful advice for doing things better.

Key information users need to know.

Urgent info requiring immediate attention.

Advises about risks or negative outcomes.

Check this out, it's a test post!

Useful information with formatting and links.

Helpful advice for doing things better.

Key information users need to know.

Urgent info requiring immediate attention.

Advises about risks or negative outcomes.

I honestly can't remember when I was first introduced to the idea of RSS/Atom feeds, and the idea of having an aggregator or reader of some description to keep up with updates on your favourite sites. It's got to be over 25 years ago now. I can't remember what I used either, but I remember using one or two readers that ran locally, right up until I met Google Reader. Once I discovered that I was settled.

As time moved on and I moved from platform to platform, and wandered into the smartphone era, I stuck with Google Reader (and the odd client for it here and there). It was a natural and sensible approach to consuming news and updates. It also mostly felt like a solved problem and so felt nice and stable.

So, of course, I was annoyed when Google killed it off, like so many useful things.

When this happened I dabbled with a couple of alternatives and, at some point, finally settled on TheOldReader. Since then it's been my "server" for feed subscriptions with me using desktop and mobile clients to work against it.

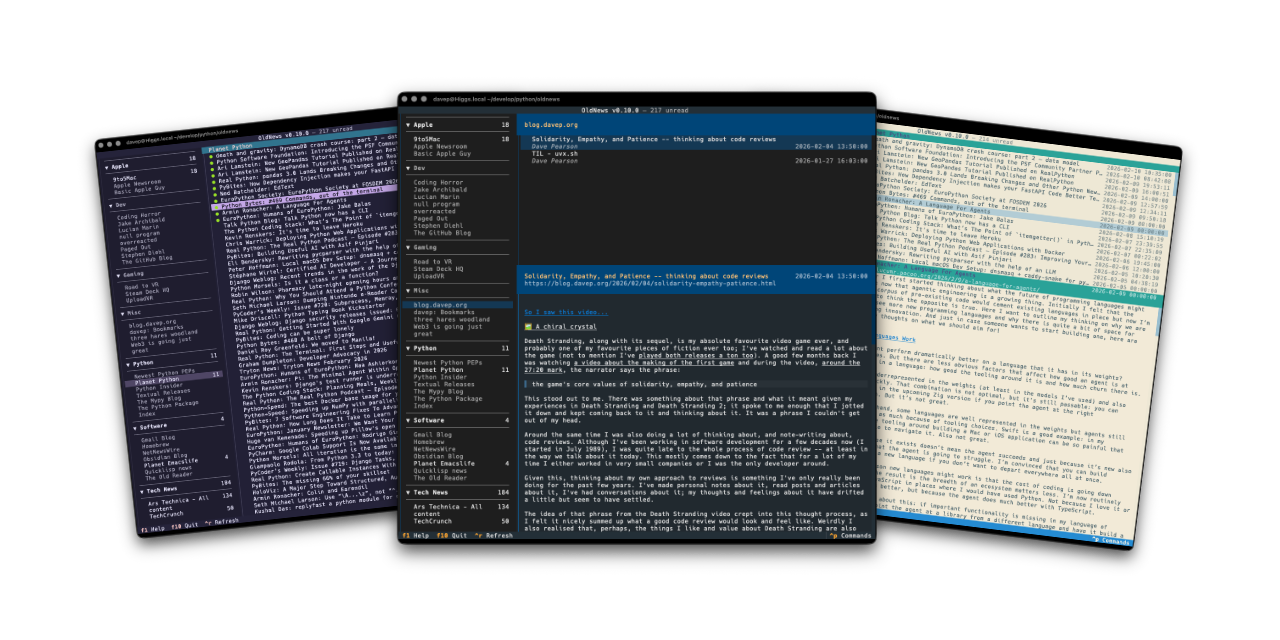

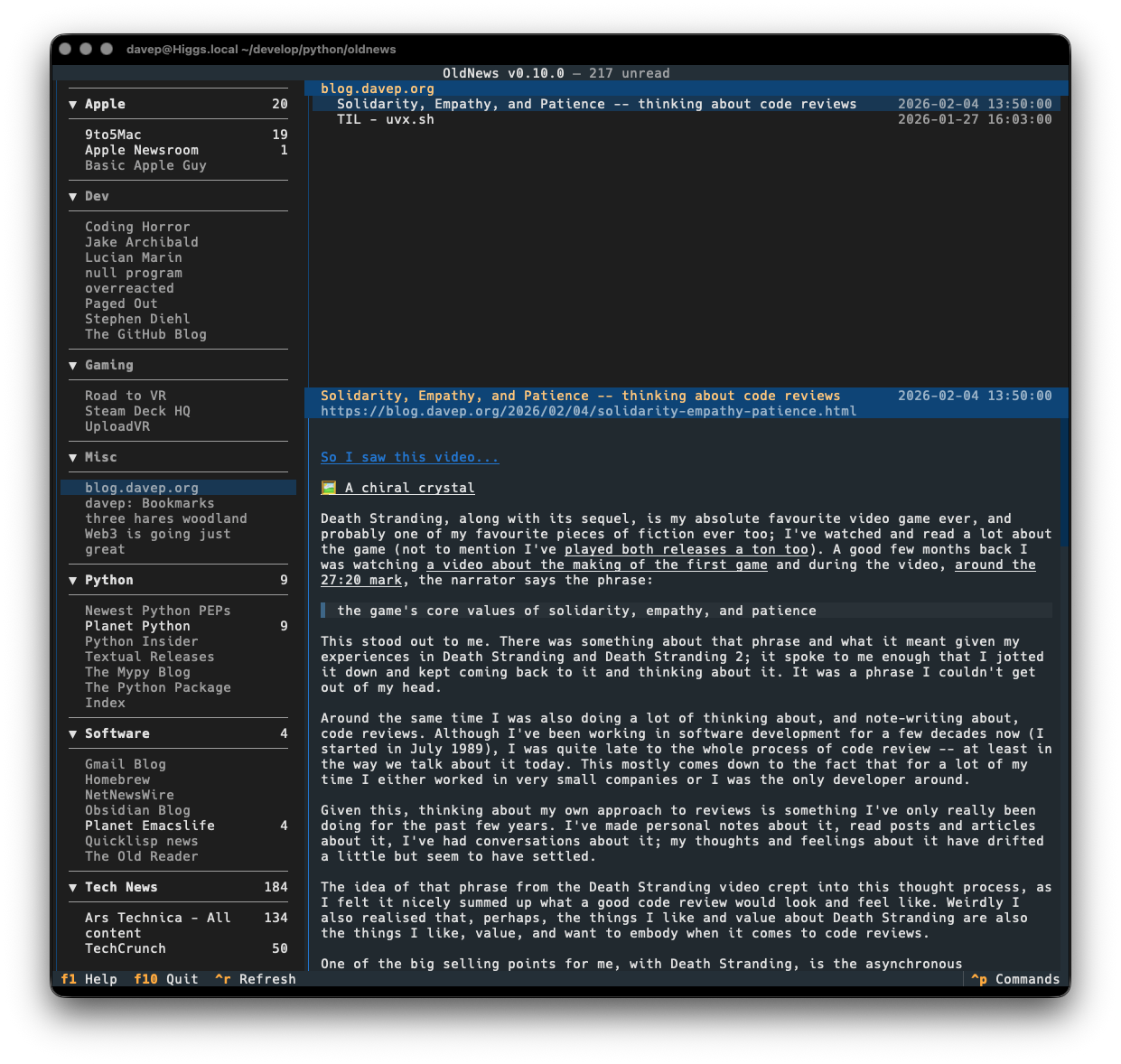

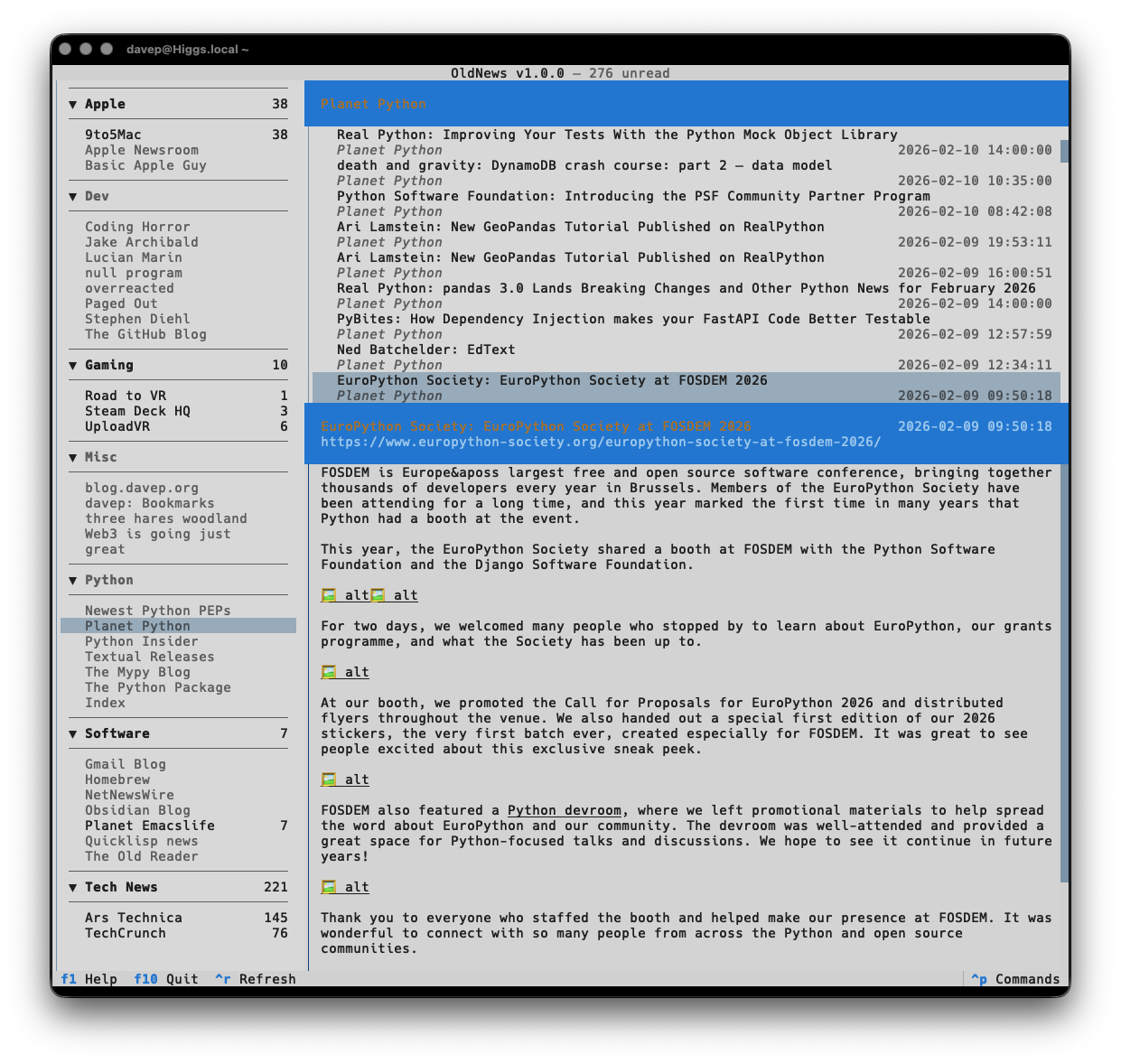

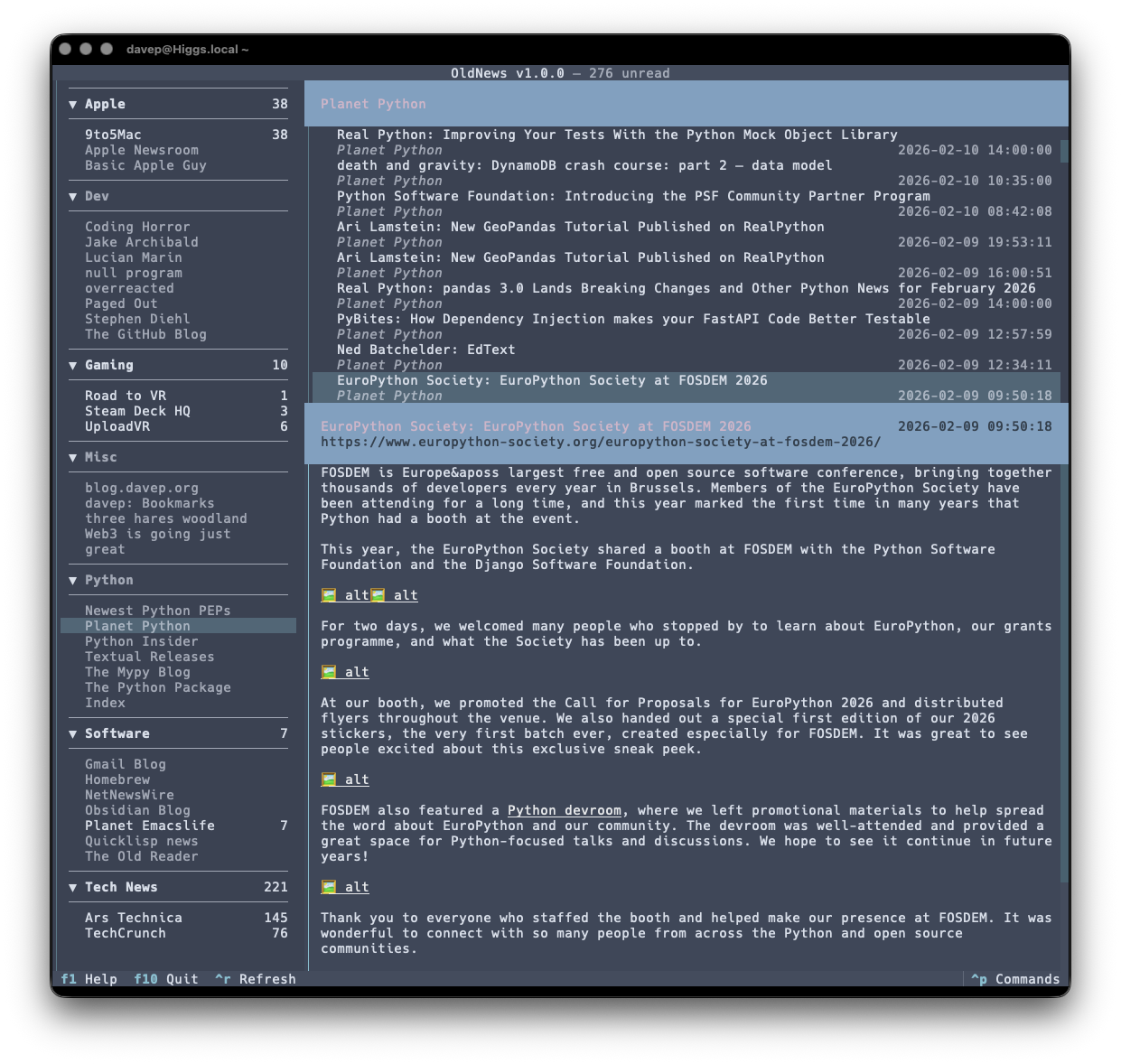

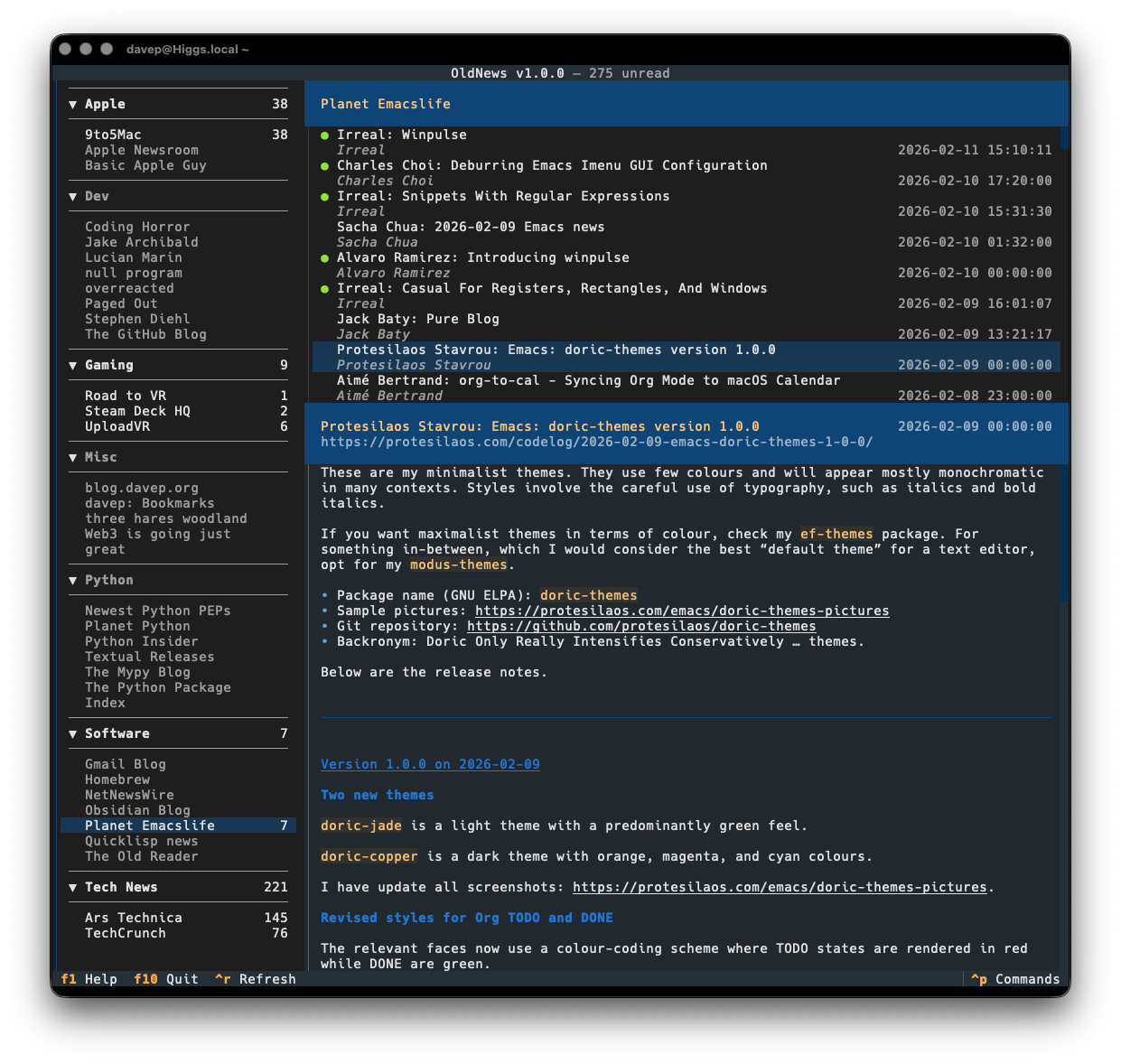

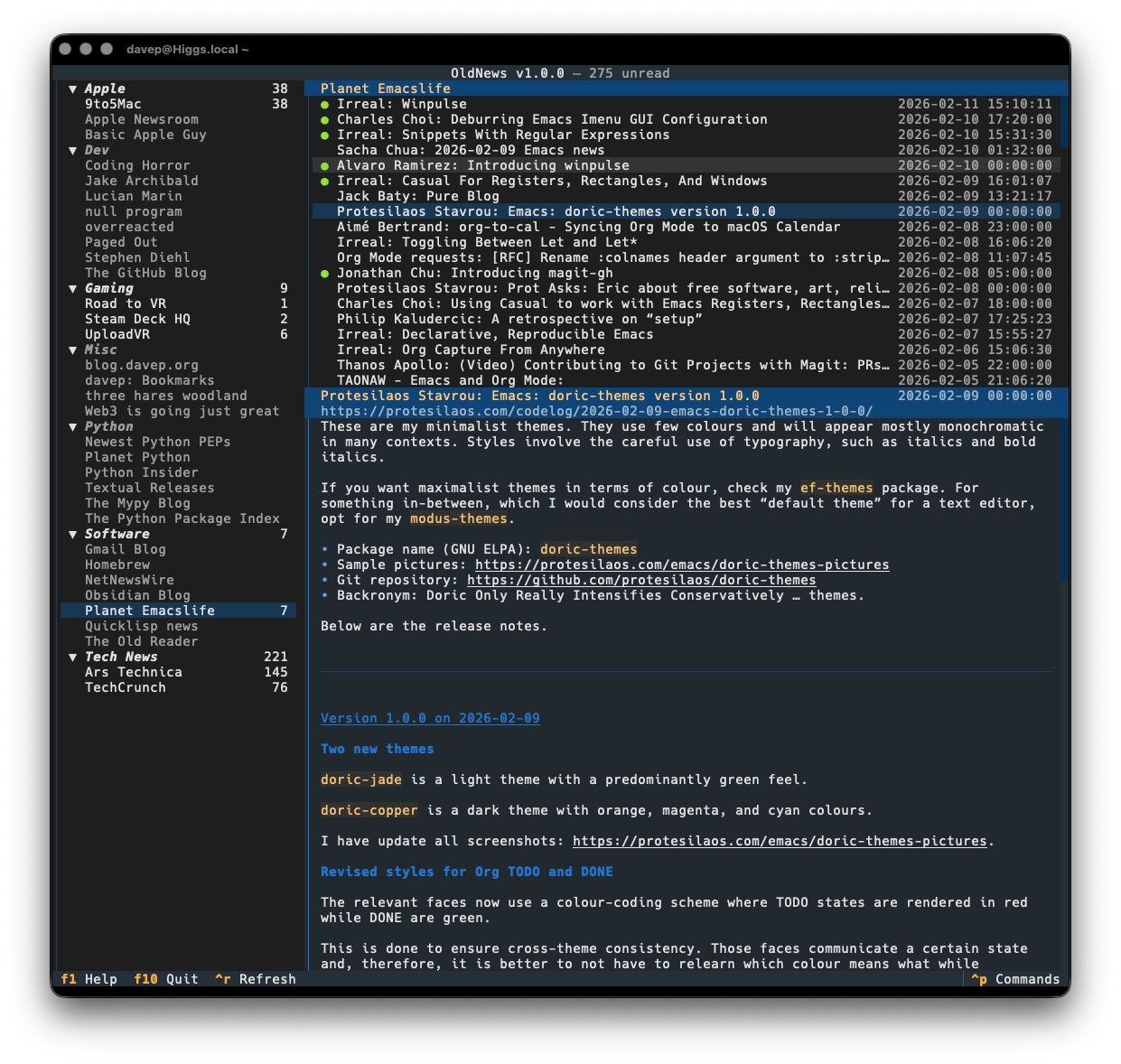

But... I never found anything that worked for me that ran in the terminal. Given I've got a thing for writing terminal-based tools it made sense I should have a go, and so OldNews became my winter break project.

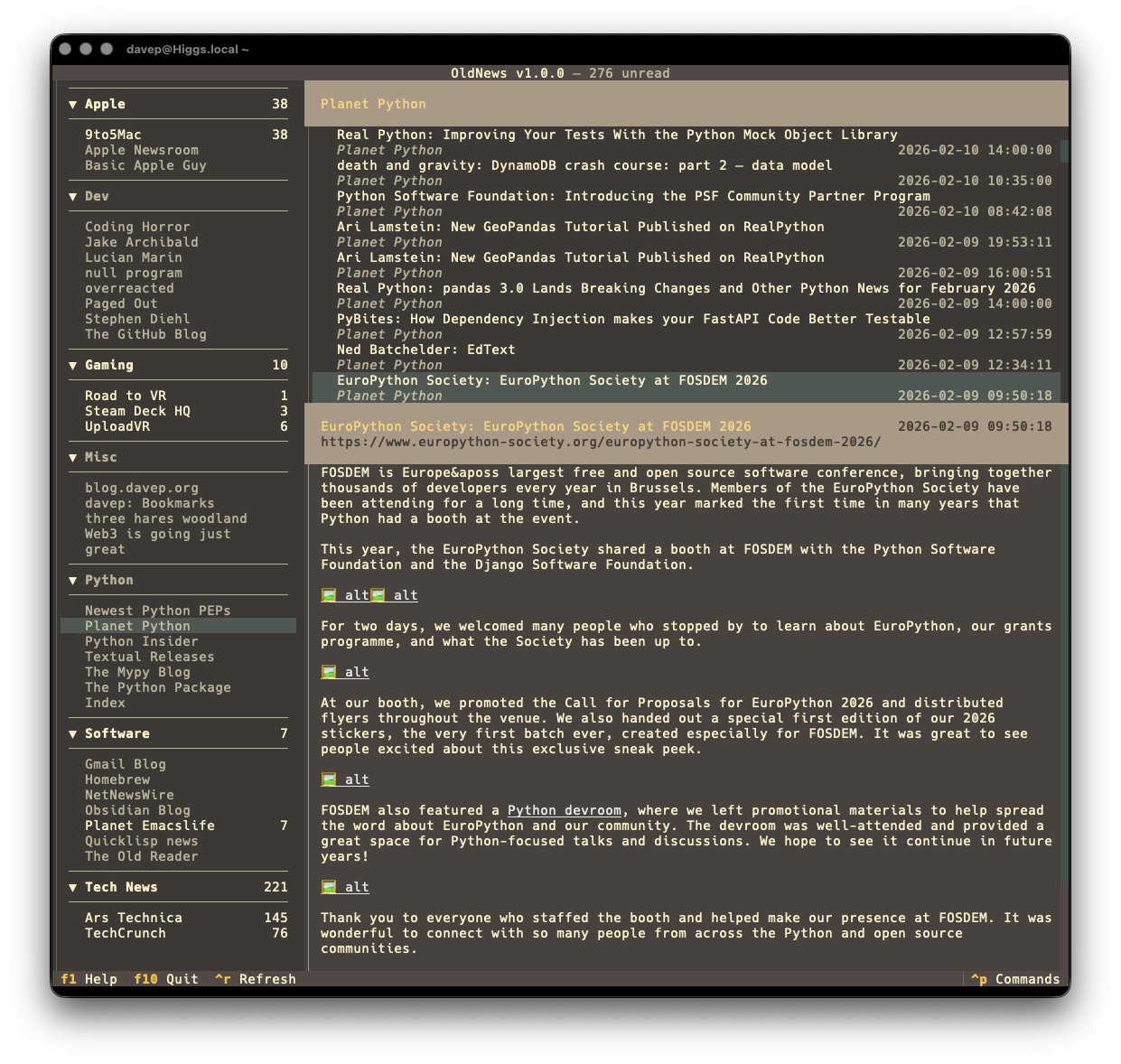

I've written it as a client application for the API of TheOldReader, and only for that, and have developed it in a way that works well for me. All the functionality I want and need is in there:

Currently there's no support for starring feeds or interacting with the whole "friend" system (honestly: while I see mention of it in the API, I know nothing of that side of things and really don't care about it). As time goes on I might work on that.

As with all of my other terminal-based applications, there's a rich command palette that shows you what you can do, and also what keyboard shortcuts will run those commands. While I do still need to work on some documentation for the application (although you'd hope that anyone looking for an RSS reader at this point would mostly be able to find their way around) the palette is a good place to go looking for things you can do.

Plus there's a help screen too.

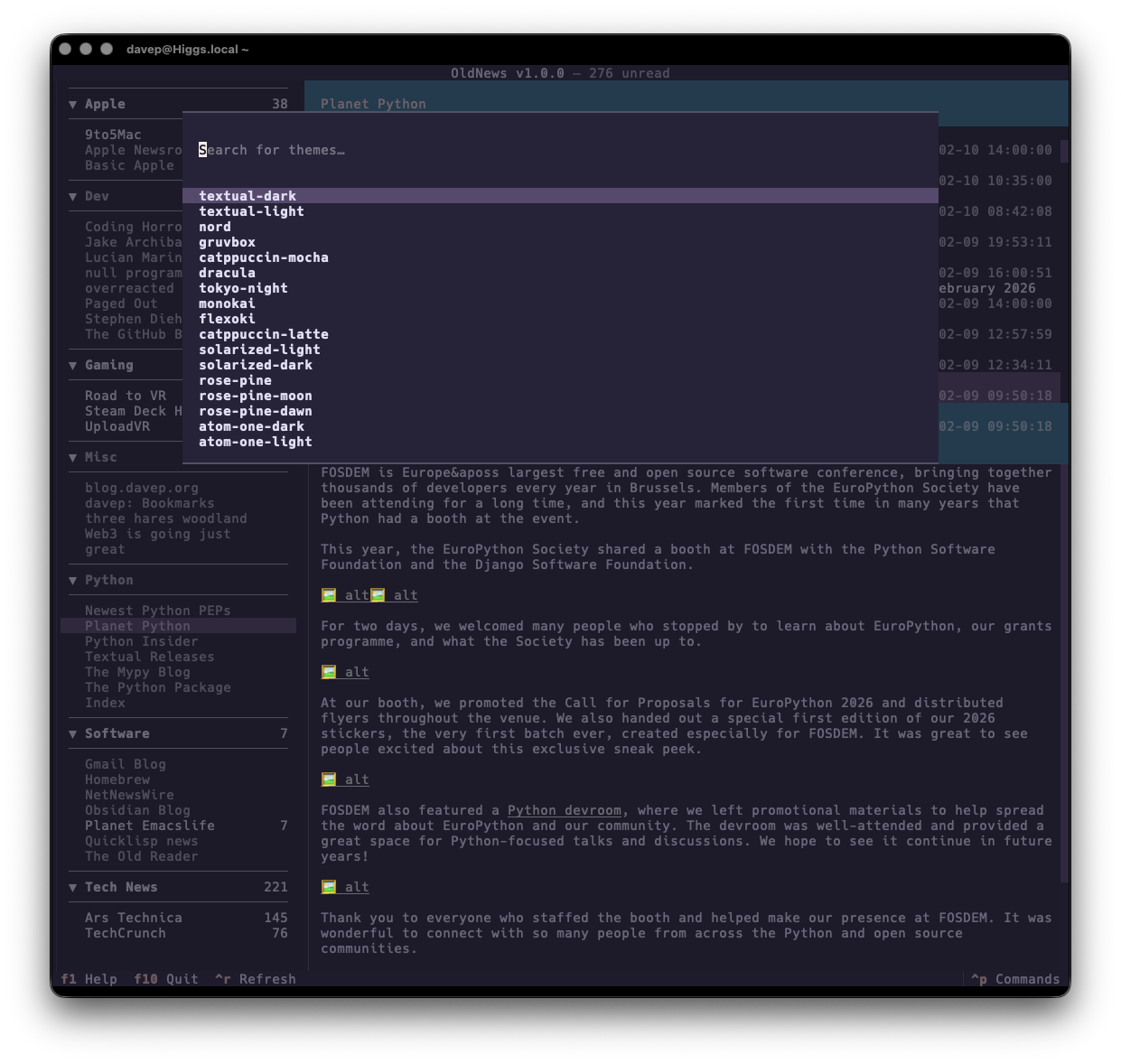

If themes are your thing, there's themes:

That's a small selection, and there's more to explore.

Also on the cosmetic front there's a simple compact mode, which toggles between two ways of showing the navigation menu, the article lists and the panel headers.

OldNews has been a daily-driver for a wee while now, while also under active development. I think I've covered all the main functions I want and have also shaken out plenty of bugs, so today's the day to call it v1.0.0 and go from there.

If you're a user of TheOldReader and fancy interacting with it from the

terminal too then it's out there to try out. It's licensed GPL-3.0 and

available via GitHub and also via

PyPI. If you have an environment that

has pipx installed you should be able to get up and running with:

$ pipx install oldnews

It can also be installed using

uv:

uv tool install oldnews

If you don't have uv installed you can use uvx.sh to

perform the installation. For GNU/Linux or macOS or similar:

curl -LsSf uvx.sh/oldnews/install.sh | sh

or on Windows:

powershell -ExecutionPolicy ByPass -c "irm https://uvx.sh/oldnews/install.ps1 | iex"

Once installed, run the oldnews command.

Hopefully this is useful to someone else; meanwhile I'll be using it more and more. If you need help, or have any ideas, please feel free to raise an issue or start a discussion.

Death Stranding, along with its sequel, is my absolute favourite video game ever, and probably one of my favourite pieces of fiction ever too; I've watched and read a lot about the game (not to mention I've played both releases a ton too). A good few months back I was watching a video about the making of the first game and during the video, around the 27:20 mark, the narrator says the phrase:

the game's core values of solidarity, empathy, and patience

This stood out to me. There was something about that phrase and what it meant given my experiences in Death Stranding and Death Stranding 2; it spoke to me enough that I jotted it down and kept coming back to it and thinking about it. It was a phrase I couldn't get out of my head.

Around the same time I was also doing a lot of thinking about, and note-writing about, code reviews. Although I've been working in software development1 for a few decades now (I started in July 1989), I was quite late to the whole process of code review -- at least in the way we talk about it today. This mostly comes down to the fact that for a lot of my time I either worked in very small companies or I was the only developer around.

Given this, thinking about my own approach to reviews is something I've only really been doing for the past few years. I've made personal notes about it, read posts and articles about it, I've had conversations about it; my thoughts and feelings about it have drifted a little but seem to have settled.

The idea of that phrase from the Death Stranding video crept into this thought process, as I felt it nicely summed up what a good code review would look and feel like. Weirdly I also realised that, perhaps, the things I like and value about Death Stranding are also the things I like, value, and want to embody when it comes to code reviews.

One of the big selling points for me, with Death Stranding, is the asynchronous multiplayer aspect of it; the reason Kojima calls it a "Strand type game". I have my game, I have my goal, but other people can indirectly affect it, either doing work in their game that leaks into mine in a beneficial way, or by leaking into mine in a way that I have to clean up. There's something really satisfying about this asynchronous collaboration. That feels similar to the collective effort of working in a single repository, each person working on their own branch or PR, sometimes in tandem, sometimes in series, sometimes to the benefit of each other and sometimes in ways that block each other.

But that's not the point here. There's a similarity if I think about it, but I don't want to get too carried away on that line of thought. It's the phrase from the video I care about; it's the approach of involving solidarity, empathy and patience I want to think about more.

This, for me, is all about where you position yourself when you approach reviewing code. I sense things only work well if you view the codebase as something with common ownership. I've worked on and with a codebase where the original author invited others in to collaborate, but where they constantly acted as a gatekeeper, and often as a gatekeeper who was resistant to their own contributions being reviewed, and it was an exhausting experience.

I believe the key here is to work against a "your code" vs "my standard" approach, instead concentrating on an "our repository" view. That's not to say that there shouldn't be standards and that they shouldn't be maintained -- there should be and they should be -- but more to say that they should be agreed upon, mutually understood to be worthwhile, and that any callout of a standard not being applied is seen as a good and helpful thing.

The driving force here should be the shared intent, and how the different degrees of knowledge and experience can come together to express that intent. If a reviewer can see issues with a submission, with a proposed change or addition to the codebase, the ideal approach is to highlight them in such a way as to make it feel like we discovered them, not that I discovered them and you should sort it out. Depending on the degree of proposed change, this might actually be expressed by (if you're using GitHub, for example) using the "Suggested Change" feature to directly feed back into the PR, or perhaps for something a little more complex, or the offer to pair up to work on the solution.

As someone who has written a lot of code, and so written a lot of bugs and made a lot of bad design choices, I feel empathy is the easiest of the three words to get behind and understand, but possibly the hardest one to actually put into practice.

When you look at a PR, it's easy to see code, to see those design choices, and to approach the reading as if you were the one who had written it, assessing it through that lens. In my own experience, this is where I find myself writing and re-writing my comments during a review. As much as possible I try and ask the author why they've taken a particular approach. It could be, perhaps, that I've simply missed a different perspective they have. If that's the case I'll learn something about the code (and about them); if that isn't the case I've invited them to have a second read of their contribution. It seems to me that this benefits everyone.

I feel that where I land with this is the idea of striving to act less like a critic and more like a collaborator, and in doing so aiming to add to an atmosphere of psychological safety. Nobody should feel like there's a penalty to getting something "wrong" in a contribution; they should ideally feel like they've learnt a new "gotcha" to be mindful of in the future (both as an author and a reviewer). Done right the whole team, and the work, benefits.

The patience aspect of this view of reviews, for me, covers a few things. There's the patience that should be applied when reading over the code; there's the patience that should be applied when walking someone through feedback and suggestions; and there's the patience needed by the whole team to not treat code reviews as a speed bump on the road to getting work over the line. While patience applies to other facets of a review too, I think these are the most important parts.

In a work environment I think it's the last point -- that of the team's collective patience -- that is the most difficult to embody and protect. Often we'll find ourselves in a wider environment that employs a myopic view of progress and getting things done, where the burn-down chart for the sprint is all that matters. In that sort of environment a code review can often be seen, by some, as a frustrating hurdle to moving that little card across that board. Cards over quality. Cards over sustainability.

It's my belief that this is one of those times where the phrase "slow down to speed up" really does apply. For me, review time is where the team gets to grow, to own the project, to own the code, to really apply the development and engineering principles they want to embody. Time spent on a review now will, in my experience, collectively save a lot more time later on, as the team becomes more cohesive and increasingly employs a shared intuition for what's right for the project.

The thing with code reviews, or any other team activities, is they don't exist in a vacuum. They take on the taste and smell of the culture in which they operate. It's my experience that it doesn't matter how much solidarity, empathy or patience you display during your day-to-day, if it's counter to the culture in which you work it's always going to be exhausting, it's always going to feel like a slog.

If leadership in technology, in software engineering, were to show more of these three basic qualities, they'd start to appear like they realise that they're working with actual humans, not producers of code; and I think we need more of that now than at any time in the history of coding.

Since I first saw that video, and heard that phrase, and had it run around my head, I've come to feel that it's not just a good mantra for code reviews; I think it's a simple blueprint for what good tech leadership should look like. If there was more "Strand-type" leadership in my chosen industry I feel it would be more open, more accessible, would offer more psychological safety and ultimately would result in teams, and projects, that thrive.

Or software engineering, if you prefer, but that's a whole other blog post I'll never get round to writing one day. ↩

After having knocked up obs2nlm the other day I realised there was another source of sources available to me that might be fun to throw into NotebookLM: one or more of the Norton Guide files in my collection!

And so, after a wee bit of hacking on a wet Sunday afternoon,

ng2nlm was born.

In terms of what it does, it's pretty much the same as obs2nlm, only it

uses ngdb to read the contents of a Norton Guide

and turn it into a single Markdown file which can then be used as a source

in NotebookLM.

So far it seems to be working a treat.

Here I grabbed the guide to assembly language Norton Guide, and the DOS interrupts Norton Guide, turned them into sources, created a notebook and let it do its thing.

I can't vouch for how valid the answer to my question is -- it's a long time since I wrote any 8086 assembler code and it's a moment since I last had to dig into DOS interrupts and the like -- but I like the result.

Probably the biggest issue I see at the moment is with the code examples: it seems to have a habit of adding some sort of citation marker that links to nowhere when it's emitting code. I think this is down to the instructions I've given it in the source I output, at least that's what it's suggesting when I ask it:

Me: What are all the numbers in square brackets for?

NotebookLM: The numbers in square brackets are passage indices used to cite which specific part of the sources supports each statement [Instruction]. Within the source files themselves, these markers identify distinct entries or sections within the Norton Guide databases.

Given I am trying to encourage it to cite its sources, I think this is where the confusion comes from. In "normal" paragraphs it does do a good job of citing its source and linking to it:

so presumably, when it "thinks" it's outputting code it doesn't do the markup to actually do the linking, and so things end up looking a little confused.

If I ask that citations aren't included in the code, this does seem to have the desired effect:

So, given this, perhaps I can use the

--additional-instructions

switch for the particular source to encourage it to not add citation links

to code? Or of course I could tweak ng2nlm itself to include that

instruction to start with. While it's a little specific to one use case,

Norton Guide files do tend to be coding-related so it could make sense.

Anyway, in the very unlikely event that you have a need to turn one or more

Norton Guide files into sources to throw at NotebookLM or similar tools:

ng2nlm exists.

I'm sure I've mentioned a couple of times before that I've become quite the fan of Obsidian. For the past few years, at any given point, I've had a couple of vaults on the go. Generally I find such vaults a really useful place to record things I'd otherwise forget, and of course as a place to go back and look things up.

But... even then, it's easy enough to forget what you might have recorded and know that you can even go back and look things up. Also I tend to find that I can't quite figure out a good way of getting a good overview of what I've recorded, over time.

Meanwhile: I've been playing around with Google's NotebookLM as a tool to help research and understand various topics. After doing this with my recent winter break coding project (more on that in the future) I realised I really should get serious about taking this approach with my Obsidian Vaults.

I'm sure this is far from novel, I'm sure lots of people have done similar things already; in fact I'd quickly dabbled with the idea a few months ago, had a bit of a laugh at some of the things the "studio" made of a vault, and promptly forgot about it.

This time though I got to thinking that I should try and take it a little more seriously.

And so obs2nlm was born.

The idea is simple enough: enumerate all the Markdown files in the vault, wrap them in boundary markers, add some instructions to the start of the file to help NotebookLM "comprehend" the content better, throw in a table of contents to give clues to the structure of the vault, and see what happens when you use the resulting file as a source.

So far it's actually turning out to be really helpful. I've been using it to get summaries regarding my work over the past 18 months or so and it's helped me to consolidate my thoughts on all sorts of issues and subjects.

It's not perfect, however. I've had it "hallucinate" some stuff when making things in the studio (most notably in the slide deck facility); for me though I find this an acceptable use of an LLM. I know the subject it's talking to me about and I know when it's making stuff up. This, in turn, makes for a useful lesson in how and when to not trust the output of a tool like this.

Having tested it out with a currently-active vault, I'm now interested to find out what it'll make of some of the archived vaults I have. Back in 2024 I wrote a couple or so tools for making vaults from other things and so I have a vault of a journal I kept in Journey for a number of years, a vault of a journal I'd kept before then in Evernote, and I also have a vault of all the tweets I wrote before I abandoned Twitter. I also have a vault that was dedicated to recording the daily events and thoughts of my time working at Textualize. It's going to be fun seeing what NotebookLM makes of each of those; especially the last one.

Anyway, if Obsidian is your thing, and if you are dabbling with or fancy dabbling with NotebookLM, perhaps obs2nlm will be handy for you.

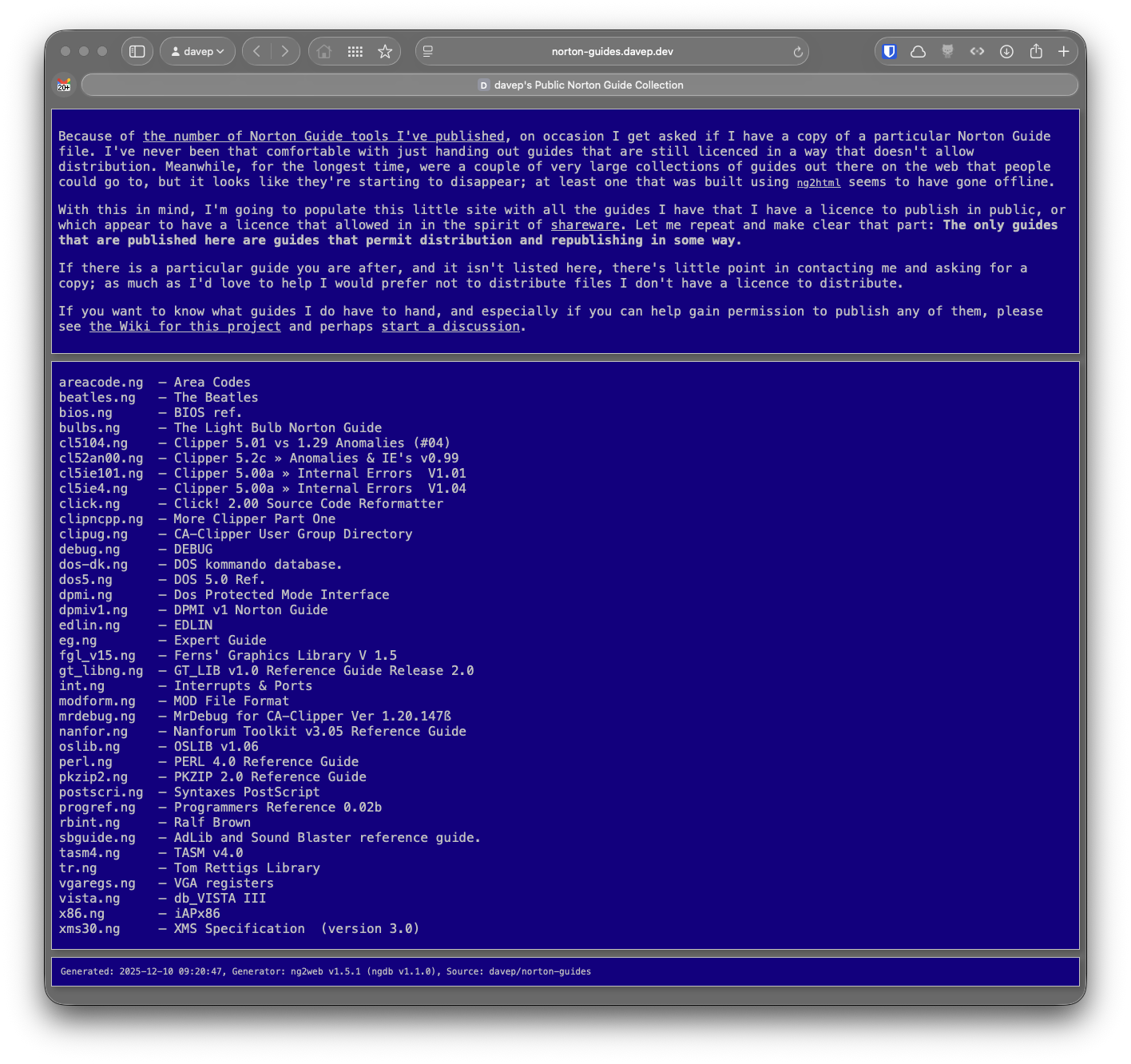

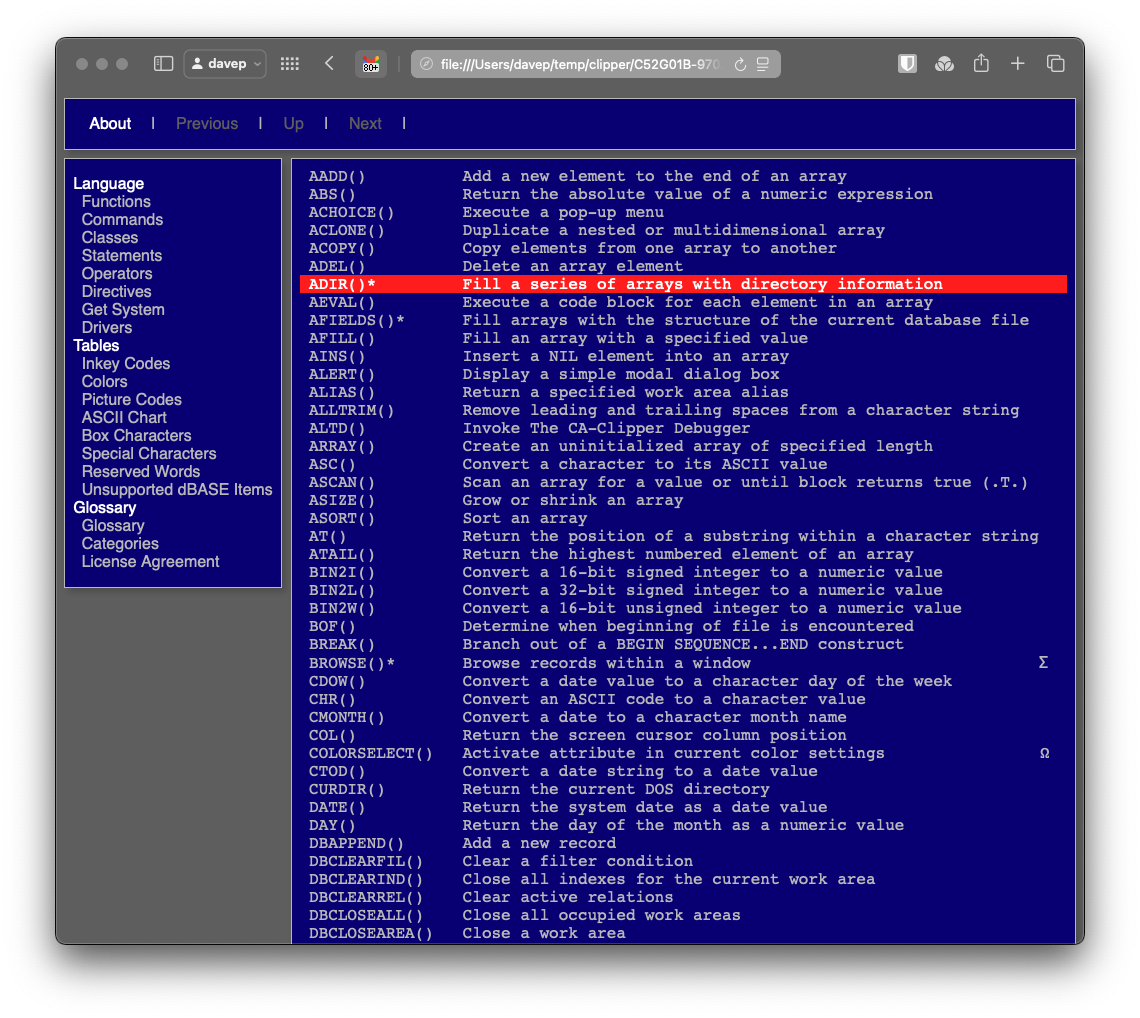

As I've mentioned a few times on this blog, I've long had a bit of a thing for writing tools for reading the content of Norton Guide files. I first used Norton Guides back in the early 1990s thanks to the release of Clipper 5, and later on in that decade I wrote my first couple of tools to turn guides into HTML (and also wrote a Windows-based reader, then rewrote it, wrote one for OS/2, wrote one for GNU/Linux, and so on).

One tool (ng2html) got used by a few

sites on the 'net to publish all sorts of guides, but it's not something I

ever got into doing myself. Amusingly, from time to time, because I had a

credit on those sites as the author of the conversion tool, I'd get random

emails from people hoping I could help them with the topic of whatever guide

they'd been reading. Sometimes I could help, often not.

From what I've recently been told two of the biggest sites for this sort of thing (they might even have been the same site, or one a copy of the other, I didn't really dive into them too much and wasn't sure who was behind them anyway) have long since gone offline. This means that, as far as I can tell, a huge collection of knowledge from the DOS days is a lot harder to get to, if it hasn't disappeared altogether.

This makes me kind of sad.

Edit to add: digging a little, one of the sites was called

www.clipx.netand it looks to have long-since gone offline. It is on archive.org though. The other wasx-hacker.orgwhich, digging a wee bit more, seems to have been a copy of what was on clipx.net.

So I had an idea: having recently polished up my replacement for ng2html, why not use that to build my own site that publishes the guides I have? So I set about it.

There's one wrinkle to this though. While the other sites seemed to just publish every NG file they got their hands on, I'd prefer to try and do it like this: publish every guide I have in my collection that I have a licence or permission to publish; or as near as possible1

Given all of this, norton-guides.davep.dev has been born. The repository that drives it is on GitHub, and I have a wiki page that lists all the guides I have that I could possibly publish, showing what I know about the copyright/licence of each one and what the publishing state is.

So with this, I'm putting out a call for help: if you remember the days of Norton Guide help files, if you have Norton Guide help files I don't have, and especially if you are the copyright-holder of any of these files and you can extend me the permission to open them up, or if you know the right people and can get me in touch with them, DROP ME A LINE!

I'd also love to have others join me in this... quest. So if you want to contribute to the repository and help build it up I'd also love to hear from you.

I will possibly be a little permissive when it comes to things that I believe contain public domain information to start with. ↩

Back in the very early days of my involvement with

Textualize, while looking for fun things to

build to test out the framework and find problems with it, I created

textual-astview. The idea was

pretty simple: exercise Textual's

Tree widget by using it to

display the output of Python's abstract syntax tree

module.

While the code still works, Textual has moved on a lot, as has my approach to building applications with Textual, and so I've been wanting to do a ground-up rewrite of it. At the same time I was also thinking that it might be interesting to build a tool that provides other ways of understanding how your Python source gets turned into runnable code; with this in mind I've ended up building a terminal-based application called DHV.

The idea is pretty straightforward: you type in, paste in, or load up, Python code, and you get a real-time display of what the resulting bytecode and abstract syntax tree would be.

If you've ever wondered what a particular bit of code looks like under the

hood, or wondered if one particular approach to a problem is "more

efficient"1 than another, or just wondered to yourself if 1+1 ends up

being a complex operation or simply gets turned into 2, this tool might be

useful to experiment and see.

As of now DHV only works with Python 3.13. The main reason for this is that

the Python dis module is a bit of a moving target and has had some

noticeable interface changes over the past few versions. When I find some

time I might work on making DHV a little more backward-compatible. But for

now keep this in mind: when you're looking at the results for some code

you're looking at what Python 3.13 (or later) would do, earlier Pythons may

differ.

DHV is licensed GPL-3.0 and available via

GitHub and also via

PyPI. If you have an environment that has

pipx installed you should be able to get up and going with:

pipx install dhv

If you're a fan of

uv and friends

you can install it like this:

uv tool install --python 3.13 dhv

I'm sure many of us have worked with that person who claims "this is more efficient" without providing any evidence; this might just be the tool to let you check that assertion. ↩

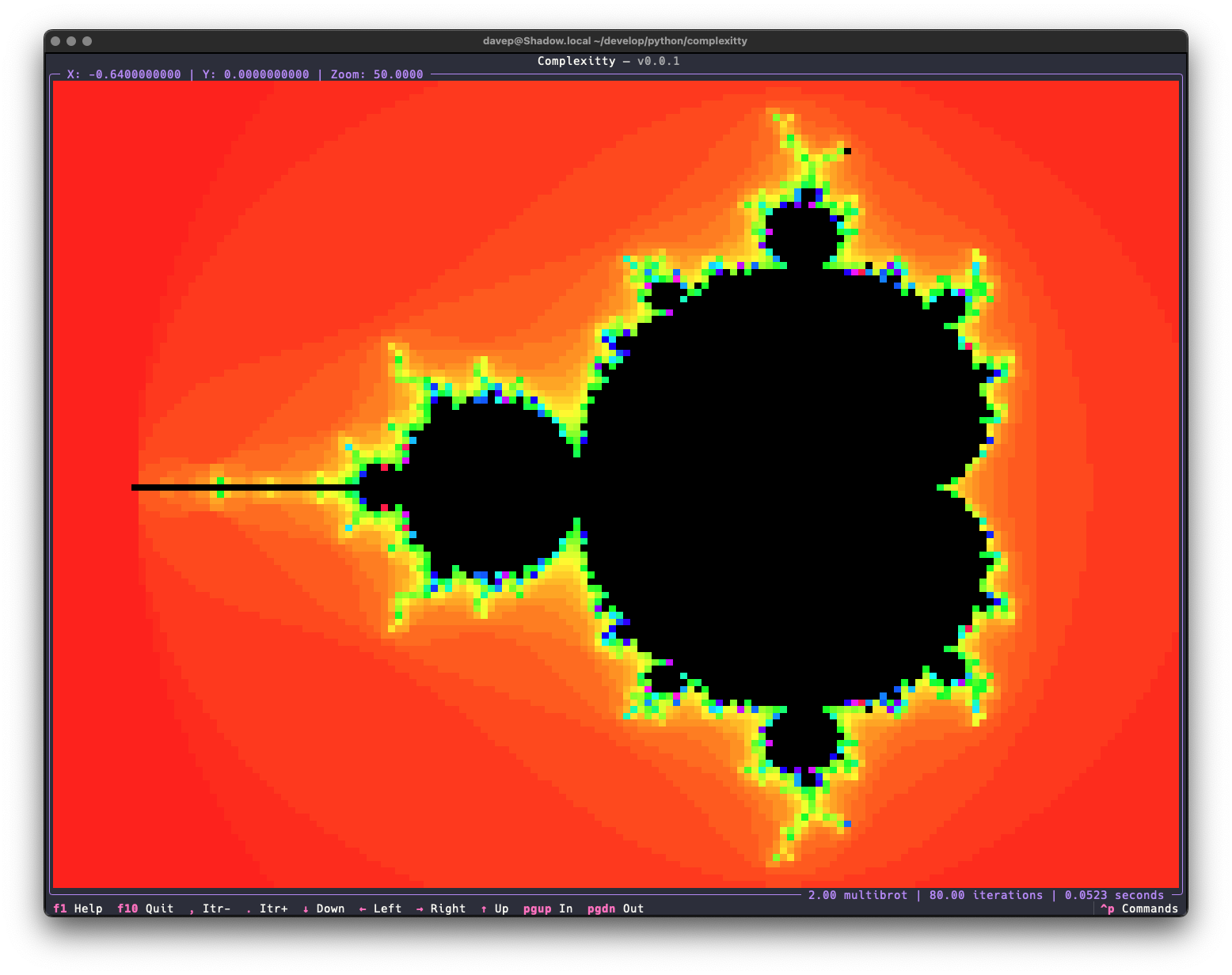

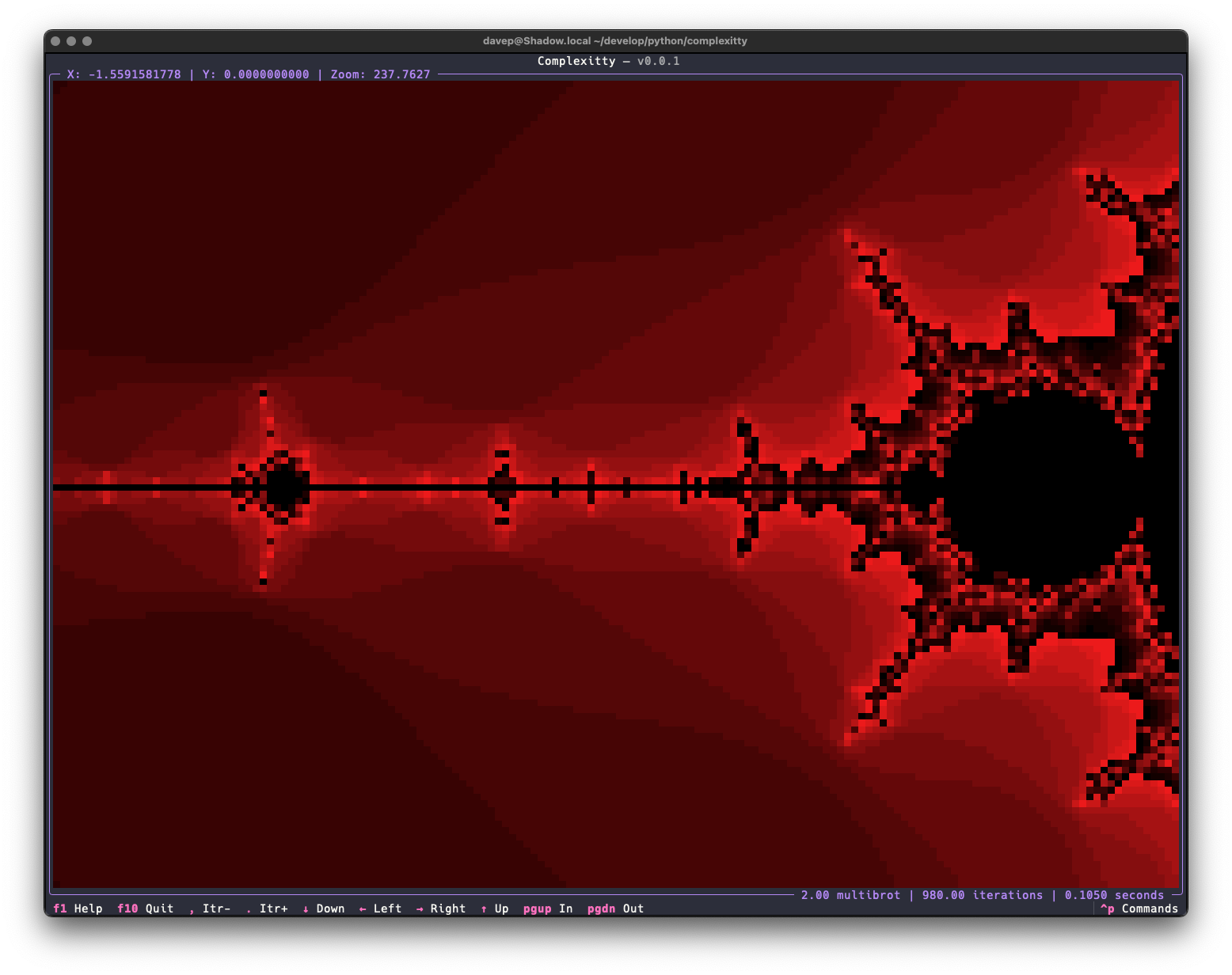

Much like Norton Guide readers or the 5x5 puzzle, code that has fun with the Mandelbrot set is another one of my goto exercises. I've written versions in many languages, and messed with plots in some different environments, as varied as in VR on the web to wearable items.

Back in the early days of my involvement with Textualize I wrote a deliberately worst-approach version using that framework. The whole thing was about taking a really silly approach while also stress-testing Textual itself. It did the job.

Later on I did a second version that targets

Textual. This time it did a

better job and was the catalyst for building

textual-canvas. This version was

intended more to be a widget that happened to come with an example

application, and while it was far more better than the on-purpose-terrible

version mentioned above, I still wasn't 100% happy with the way it worked.

Recently I did some maintenance work on textual-canvas, cleaning up the

repository and bringing it in line with how I like to maintain my Python

projects these days, and this prompted me to look back at

textual-mandelbrot and rework it too. Quickly I realised it wasn't really

sensible to rewrite it in a way that it would be backward compatible (not

that I think anyone has ever used the widget) and instead I decided to kick

off a fresh stand-alone application.

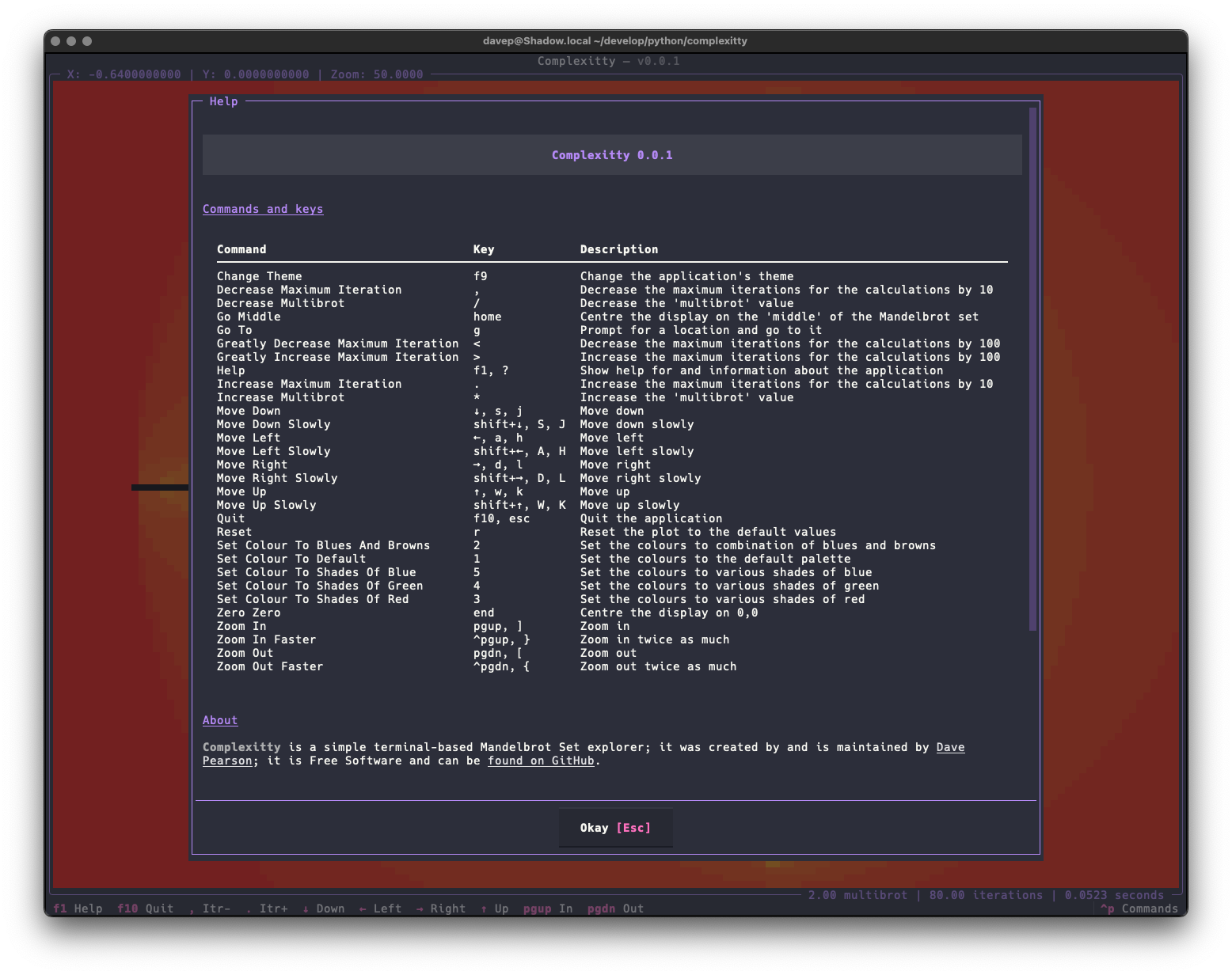

Complexitty is the result.

Right now the application has all the same features as the mandelexp

application that came with textual-mandelbrot, plus a couple more. Also

it's built on top of the common core

library I've been putting

together for all my own terminal-based Python applications. As time goes on

I'll add more

features.

As with most of my recent TUI-based projects, the application is built with comprehensive help for commands and key bindings.

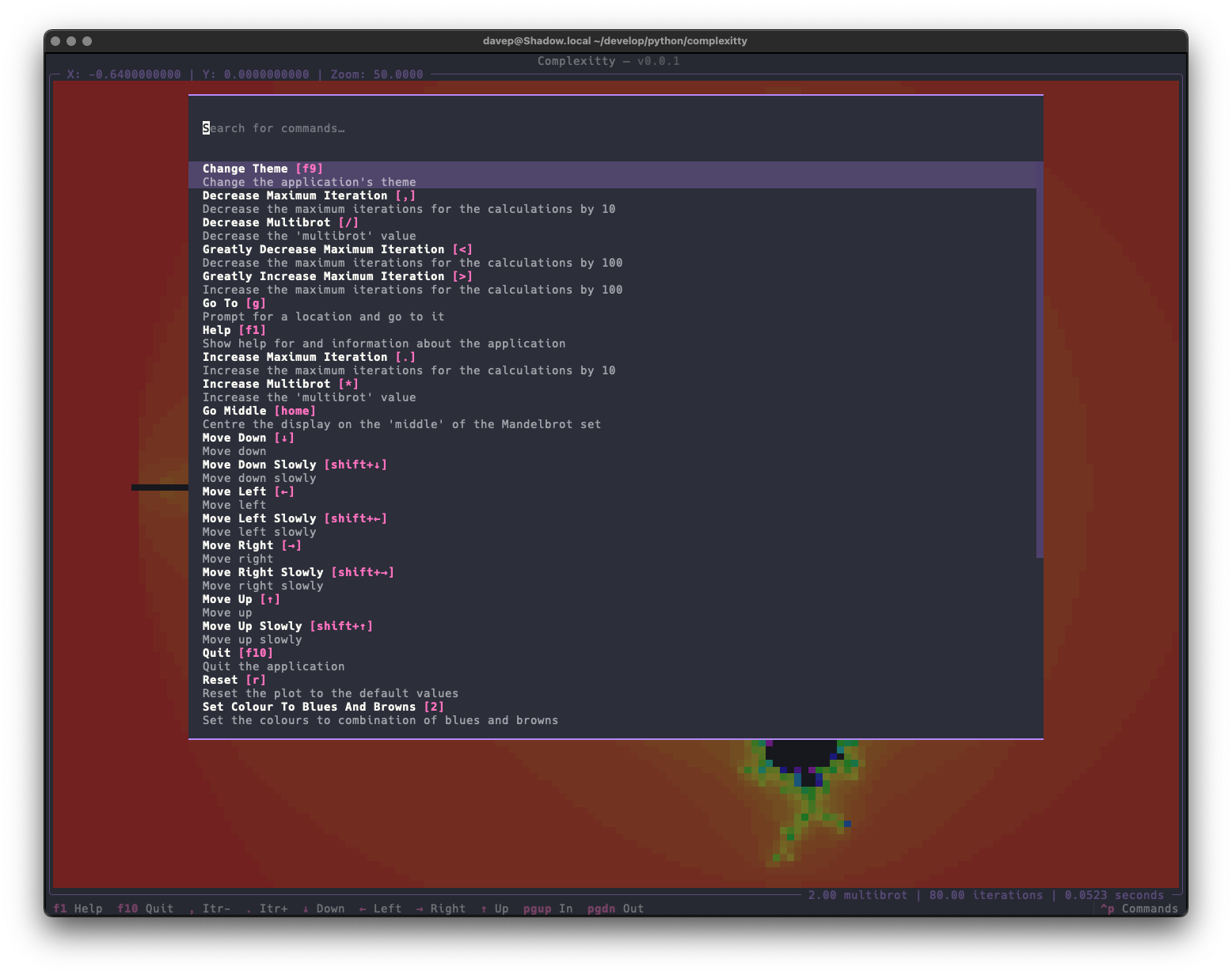

and there's also a command palette that helps you discover (and run) commands and their keyboard bindings.

Complexitty is licensed GPL-3.0 and available via

GitHub and also via

PyPI. If you have an environment that has

pipx installed you should be able to get up and going with:

pipx install complexitty

It can also be installed with

Homebrew by tapping davep/homebrew and then installing complexitty:

brew tap davep/homebrew

brew install complexitty

It pretty much all started with this:

* Revision 1.1 1996/02/15 18:57:13 davep

* Initial revision

That's from the rcs log for the source for

w3ng, a tool I wrote so

I could read Norton Guide files in my web browser, served by Apache, running

on my GNU/Linux server in my office. The tool itself was written as a

CGI tool (remember

them?).

I believe I posted about this to comp.lang.clipper and pretty quickly some

folk asked if it might be possible to do a version that would write the

whole guide as a collection of HTML files for static hosting, rather than

serving them from a cgi-bin utility. That seemed like a sensible idea and

so:

* Revision 1.1 1996/03/16 09:49:00 davep

* Initial revision

ng2html was born.

Fast forward around a quarter of a century and I decided it would be fun to

write a library for Python that reads Norton Guide

files, and a tool called ng2web was the

first test I wrote of it, designed as a more flexible replacement for

ng2html. I've tweaked and tinkered with the tool since I first created it,

but never actually "finished" it.

That's changed today. I've just released v1.0.0 of ng2web.

If turning one or more Norton Guide files into static websites seems like the sort of thing you want to be doing, take a look at the documentation.

ng2web is licensed GPL-3.0 and available via

GitHub and also via

PyPi. If you have an environment that has

pipx installed you should be able to get up and going with:

$ pipx install ng2web

It can also be installed with

Homebrew by tapping davep/homebrew and then installing ng2web:

$ brew tap davep/homebrew

$ brew install ng2web

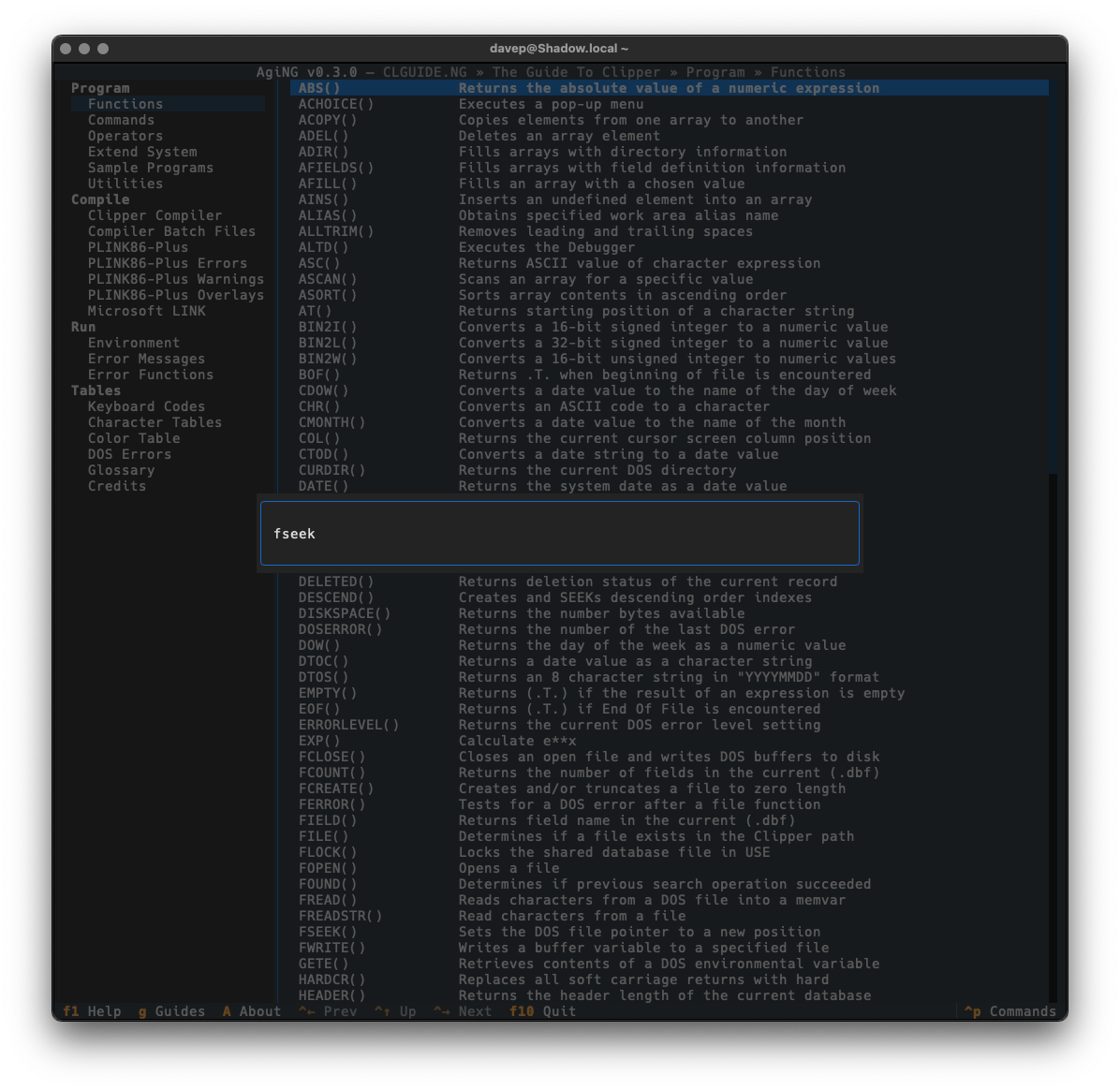

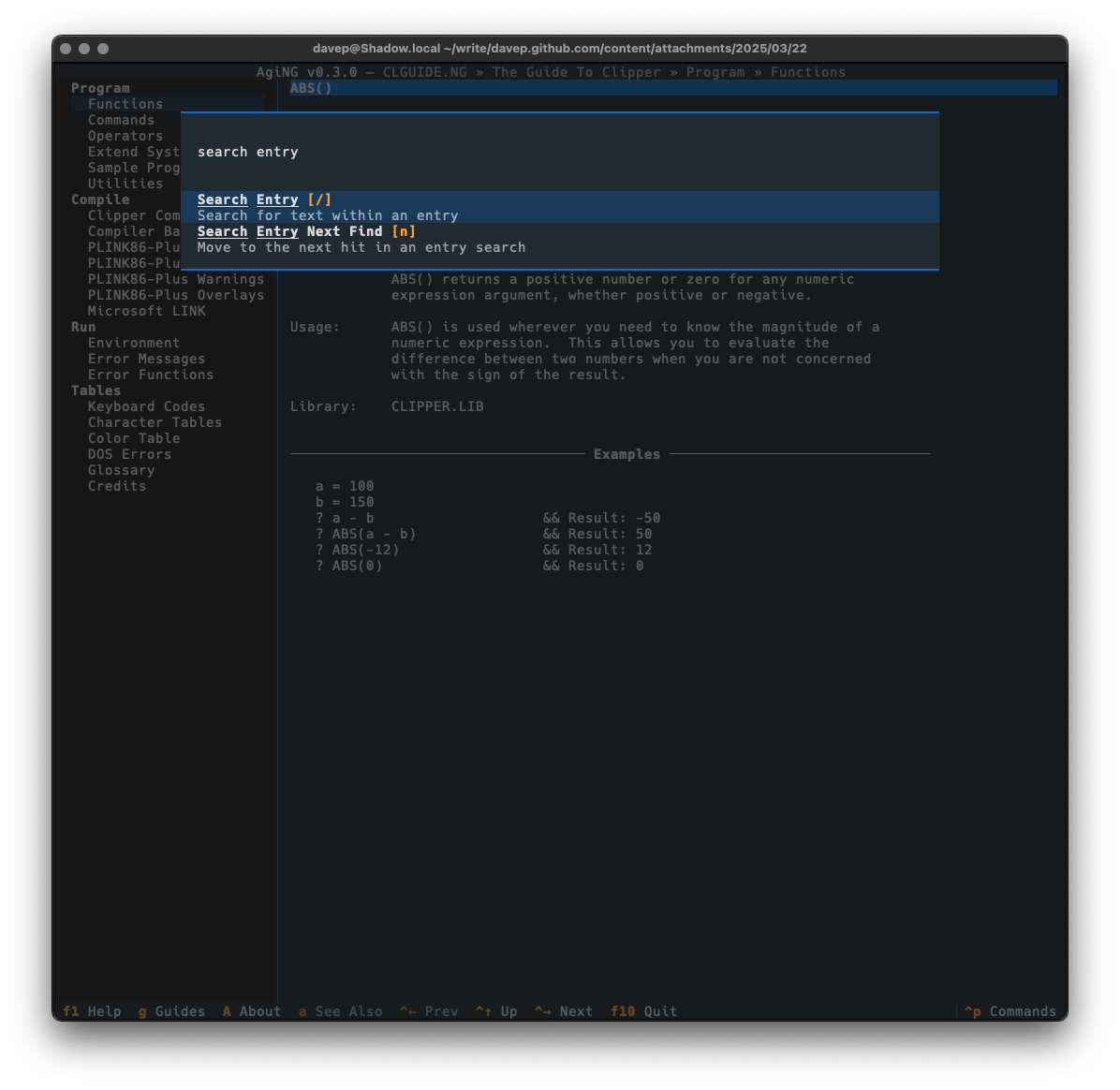

I've just released AgiNG v0.3.0. The main focus of this release was to get some searching added to the application. Similar to what I added to WEG back in the day, I wanted three types of searching:

The current entry search is done with a simple modal input, and for now the searching is always case-insensitive (I was going to add a switch for this but it sort of felt unnecessary and I liked how clean the input is).

The search is started by pressing /, and if a hit is found n will take you through all subsequent matches.

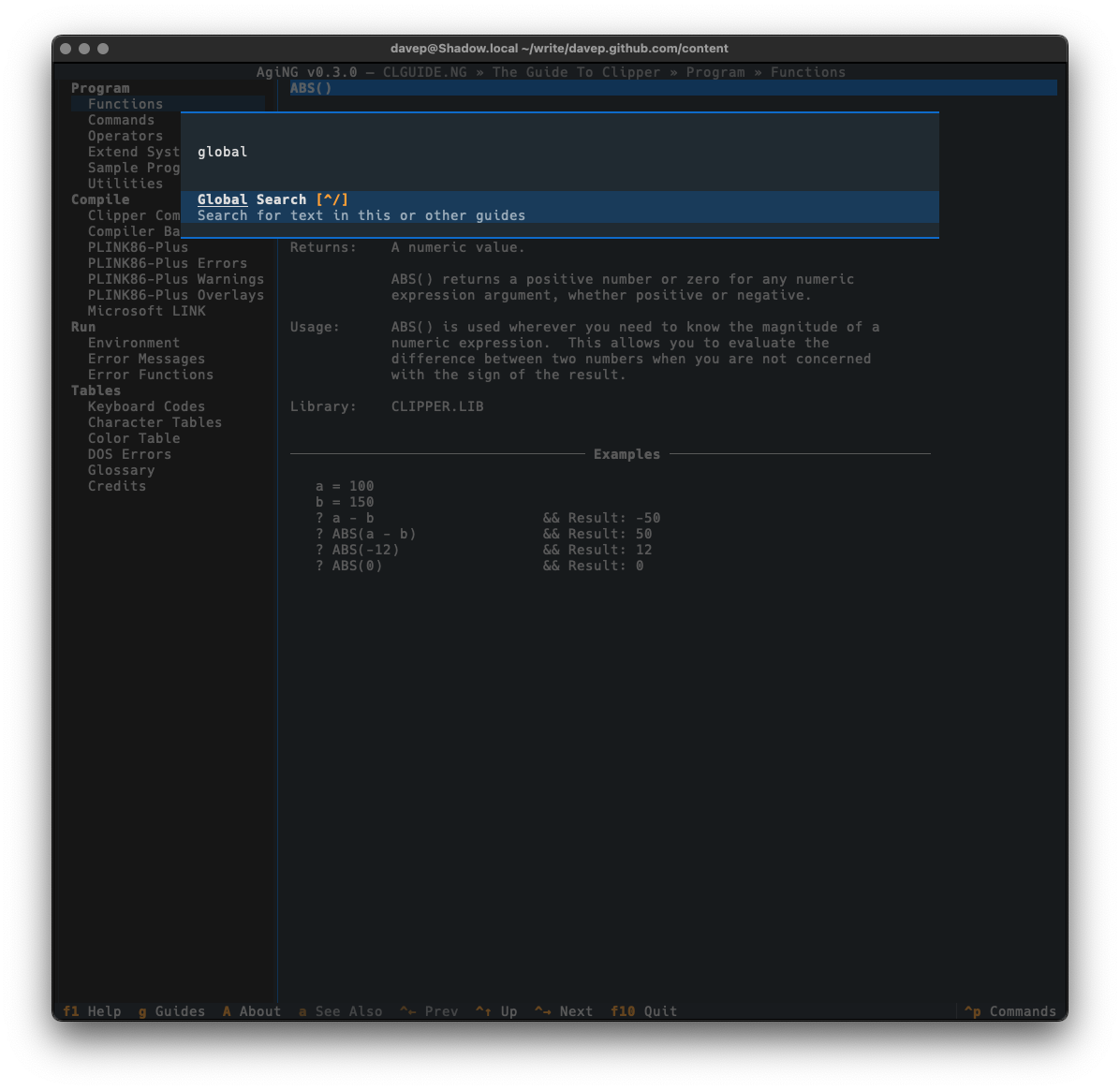

As always, if you're not sure of the keys, you'll find them in the help screen or via the command palette:

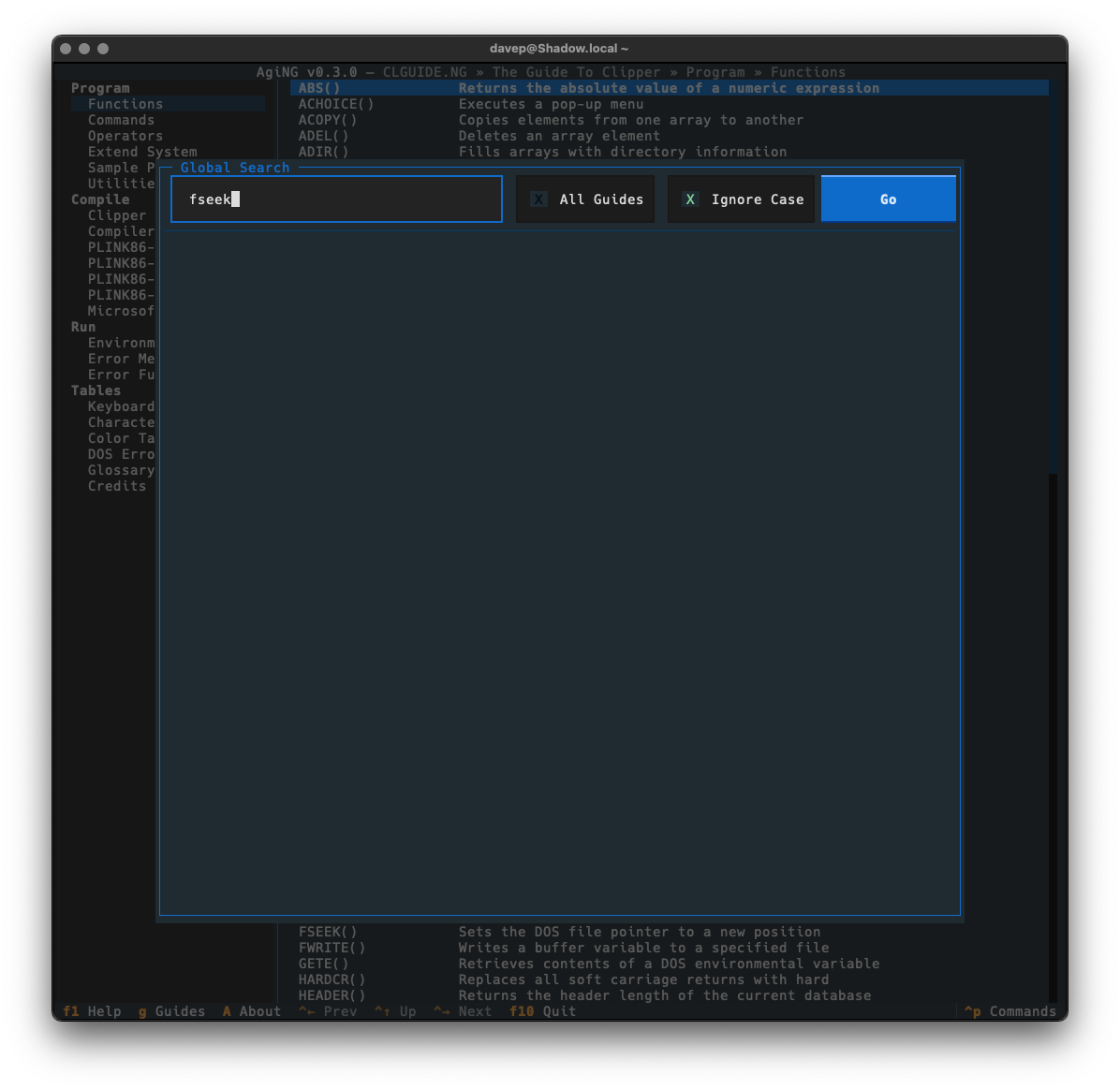

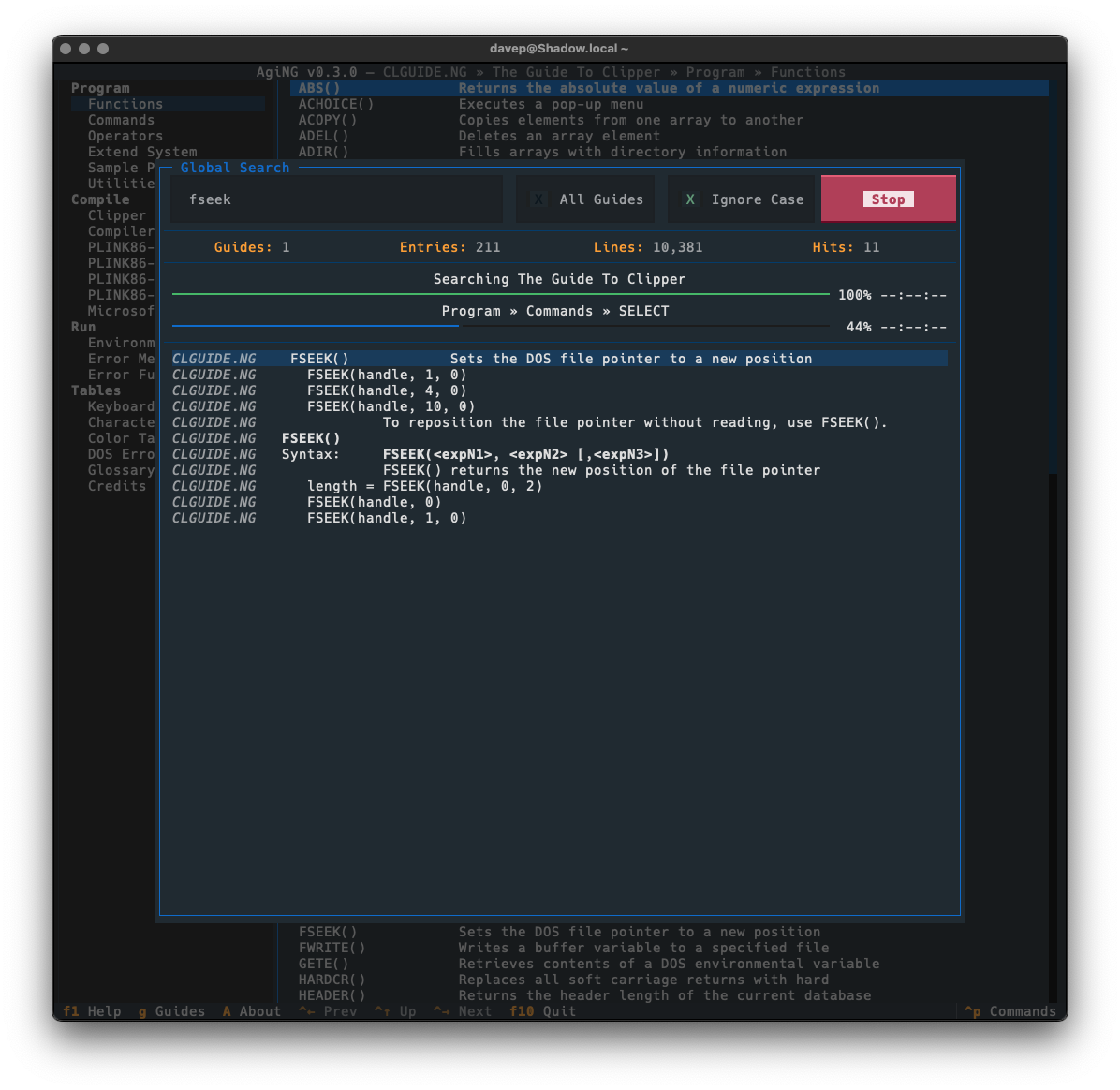

Guide-wide and all-guide searching is done in the same dialog. To search guide-wide you enter what you want to find and untick "All Guides".

With that, the search will stick to the current guide.

As will be obvious, searching all guides that have been registered with AgiNG is as simple as ticking "All Guides". Then when you search it'll take a walk through every entry of every guide you've added to the guide directory in the application.

Global searching is accessed with Ctrl+/ or via the command palette.

With this added, I think that's most of the major functionality I wanted for AgiNG. I imagine there's a few more tweaks I'll think of (for example: I think adding regex search to the global search screen could be handy), but I don't think there's any more big features it needs.

AgiNG can be installed with pip or (ideally) pipx from

PyPi. It can also be installed with

Homebrew by tapping davep/homebrew and then installing aging:

$ brew tap davep/homebrew

$ brew install aging