Both at work and at home I use Emacs by keeping a copy running all the

time, and use emacsclient to open

files inside

it

(including on remote machines thanks to a bit of

ssh and heavy use of

tramp -- I might write this up at

some point). This works really well, but does mean I tend to build up a lot

of buffers over time.

Having lots of buffers open isn't generally an issue, and if I'm working on

lots of different files in a project during the course of a hacking session

it's actually a good thing. But, quite often, I want to tidy up the buffer

list, clearing it back to near-zero buffers open. Many years ago, when I had

a "proper" tower system running 24/7, with Emacs open all the time, I'd use

clean-buffer-list as part of

midnight. Along the way

that fell out of favour with me, likely because I drifted into using

machines that had Emacs open all the time but where the machine wasn't awake

all the time.

Eventually I decided to have some fun rolling my own solution, and

nuke-buffers was born.

Rather than try and do things in an automated way, this was designed to be bound to a key (or two) and then be run when I wanted, being as harsh as possible about cleaning up the buffer list. Since first writing it it's worked well for me.

These days I tend to let the buffer list build up as I work on a new

feature, or chase down a bug, etc. Then, once I've made the final commit for

that period of focus, I'll hit the nuke-buffer key combo as the final act

of confirming that I've done the job. So not only does this help tidy my

Emacs session a bit, it also feels like a physical form of punctuation --

back in less sensible days, when I had some terrible habits, it would have

been when I'd reach for the celebratory cigarette; buffer-tidying feels far

more wholesome. ;)

The way the code works is, of course, mostly directed at how I work -- it's highly likely it wouldn't make sense for many other people. The main aim is to kill as many buffers as possible, but without disturbing anything else. The list of buffers it gathers for nuking avoids buffers that are visiting files but have unsaved content, avoids the minibuffer (obviously), avoids any "special" buffer (one that starts with a space then an asterisk), avoids the current buffer and also avoids any buffer in a list of names to avoid.

I've being using this on a daily basis for around 2.5 years now and it's done the job without ever losing me any work.

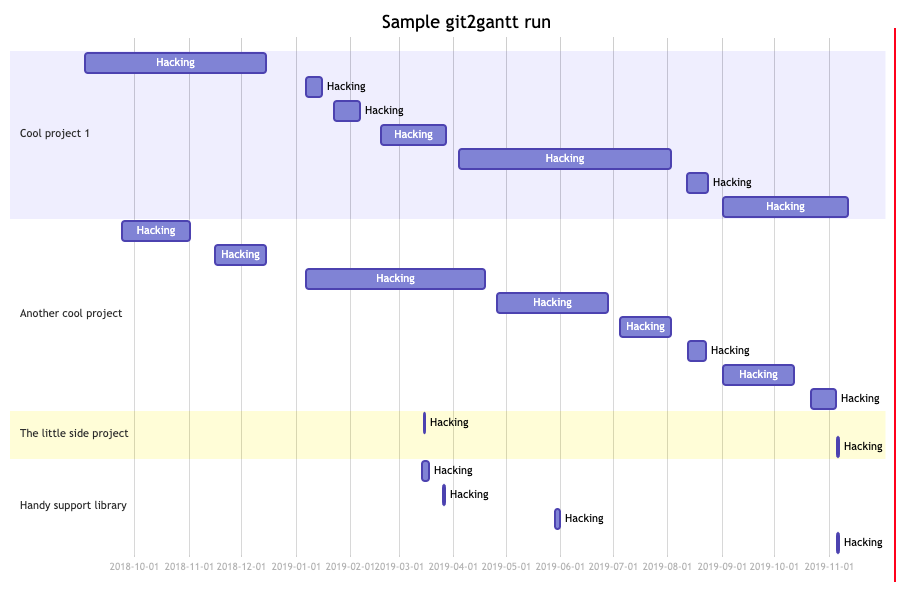

As you can see, it can be run over multiple repos at once, and there's also

an option to have it consider every branch within each repository. Another

handy option is the ability to limit the output to just one author --

perhaps you just want to document what you've done on a repo, not the

contributions of other people.

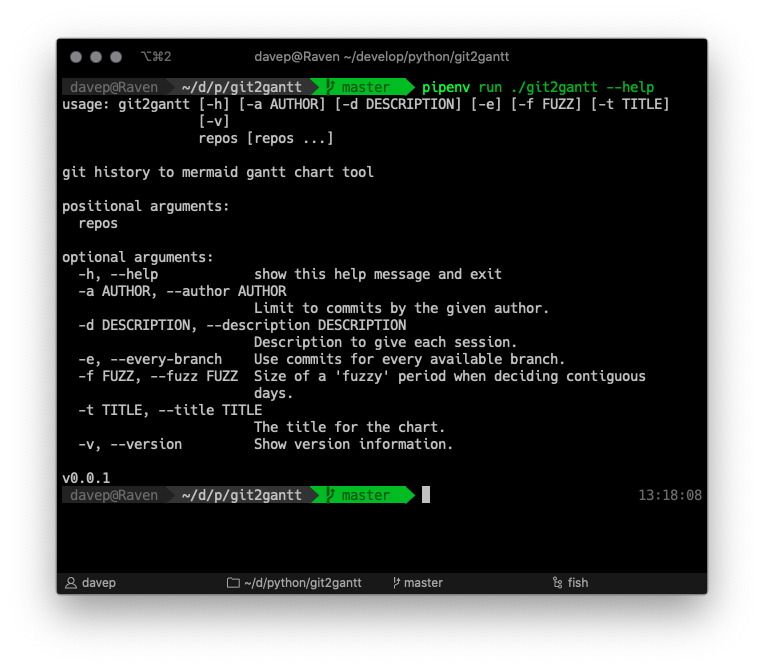

As you can see, it can be run over multiple repos at once, and there's also

an option to have it consider every branch within each repository. Another

handy option is the ability to limit the output to just one author --

perhaps you just want to document what you've done on a repo, not the

contributions of other people.